In many ways, Code Blue responders face the same challenges with pediatric patients as they do with the adult cohort. The urgency, the stakes, the need to act quickly and efficiently to deliver the best possible standard of care — these all remain the same regardless of the patient’s age.

But it’s also worth recognizing that pediatric Code Blues are specialized, have different considerations, and often require different support. Perhaps most obviously, code responders have to factor in weight-based medication and defibrillator doses for pediatric patients. Particularly during a fast-paced, high-pressure emergency event, those additional on-the-spot calculations can introduce risk and increase the likelihood of error.

But the differences don’t end there. In this article, we’ll look at 4 additional areas where there are key differences between adult and pediatric Code Blues — and what hospitals can do to optimize care for infants and children.

1. Preventing cardiac arrest

How pediatric code blues are different

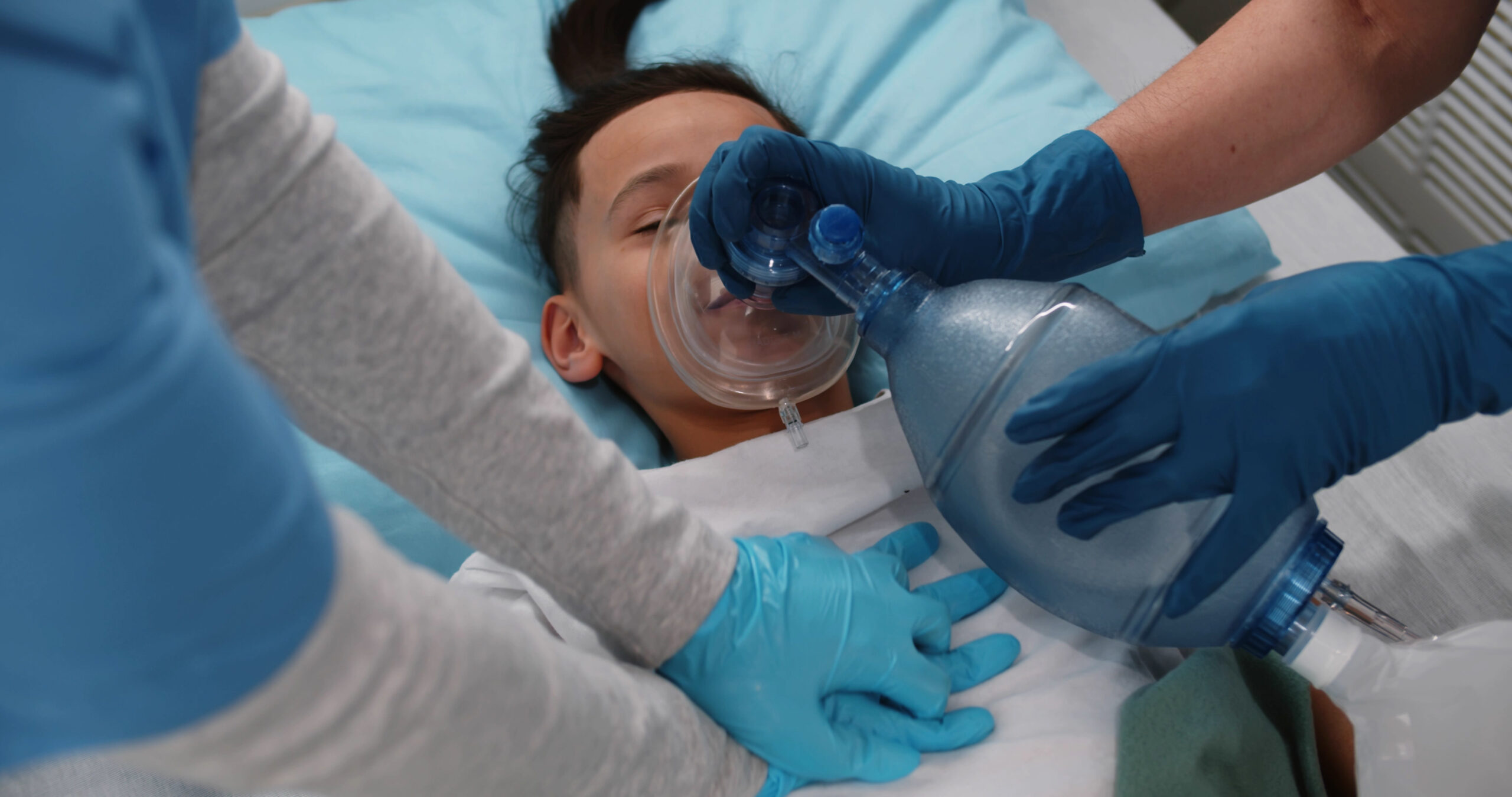

Unlike adults, arrest in pediatric patients is often respiratory in nature — not cardiac. In many ways, this is a good thing. When identified and treated early, respiratory distress/failure is generally reversible1. The catch? Once pediatric patients progress to cardiac arrest, outcomes are often poor. It becomes significantly more challenging for the code team to turn things around, achieve return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), and secure a favorable long-term outcome for the patient.1,2

Key takeaway to optimize care

- Early respiratory support is critical and often lifesaving in this population. Prioritize early identification and treatment of respiratory distress. Focusing on oxygenation, ventilation, and hemodynamics can prevent an infant or child from going into cardiac arrest — and greatly improve the likelihood of a positive outcome.

2. Discussing code status options with patients & families

How pediatric code blues are different

For adults, it’s common for conversations about code status options to occur as early as possible — often on admission. But the same conversation can be much more challenging for clinicians to initiate with parents/caregivers of a pediatric patient. Why? For one, children are often thought of as a baseline healthy population, so a conversation about end-of-life care may not come as naturally. And more importantly, the topic is particularly sensitive and distressing when discussing an infant or child.3 Providers, especially those with less experience, simply may not have the same comfort level addressing it.

But early conversations with patients and families about code status options are a key component of effective Code Blue care — regardless of the patient’s age. They help the patient or family direct end-of-life care in a way that is consistent with their preferences.3 Crucially, these conversations also give patients and their families a voice in the decision-making process in the event a life-threatening emergency occurs — something they might not have otherwise.

Key takeaways to optimize care

- Regardless of the difficulty, prioritize early discussions of code status with parents/caregivers of pediatric patients whenever possible.

- For hospitals, consider offering specific training in this area to help clinicians navigate a sensitive discussion and to minimize stress for parents/caregivers.

3. Delivering compressions to patients with a pulse

How pediatric code blues are different

Although it’s not standard of care for adults, delivering compressions to a pediatric patient with a pulse can significantly improve the likelihood of survival. Studies show that pediatric patients who are severely bradycardic and receive compressions have a 60% survival rate.4 Compare that to the only 27% chance of survival for a child who receives compressions after going into a pulseless event.4

Key takeaways to optimize care

- Deliver compressions for pediatric patients with bradycardia to support circulation.

- Reinforce this point often in mock codes and other trainings at your hospital. This is especially important since it differs from typical care for adults and may not be top of mind during a high-pressure emergency event.

4. Managing long-term complications

How pediatric code blues are different

Any patient who survives cardiac or respiratory arrest often faces an uphill battle post-ROSC, including risk of neurologic injury. For pediatric patients, long-term neurologic challenges are a particular concern for 2 reasons:

- The rate of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is especially low for pediatric victims of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Bystanders often lack adequate CPR training and are hesitant to attempt CPR on a small child. This not only makes it harder for the code team to resuscitate the patient when they arrive at the hospital, it also increases the risk of poor neurologic outcomes.5

- Even in cases of timely intervention and optimal response, there are often lasting neurologic concerns for pediatric patients. Many children require long-term neurotherapies to manage complications and effects from the arrest.

Key takeaways to optimize care

- Prioritize post-cardiac arrest care. Management of the patient post-ROSC is just as important as the timeliness and effectiveness of the code response itself. Standard post-cardiac arrest protocols apply, but care will need to be customized to meet the specific needs of the patient as well. The American Heart Association also offers resources on pediatric guidelines for post-arrest care.

- Appoint a designated spokesperson to discuss prognosis with family members post-code. This is crucial for managing expectations, as the event itself and the management afterward may affect schooling and other areas of the child’s life.6

RELATED ARTICLES

Improve pediatric Code Blue care at your hospital

Looking for more ways to support pediatric codes at your hospital? Nuvara® can help. Our CoDirector® resuscitation software helps clinicians stay on track with Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) algorithms and uses automated weight-based calculations to reduce stress and risk in the moment.

References

-

Shekhar, A. C., Campbell, T., Mann, N., et. al. (2022). Age and racial/ethnic disparities in pediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation, 145(16), 1288–1289. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.121.057508

-

Pediatric cardiac arrest overview (part 1). Accessed 5 September 2022 at: Pediatric cardiac arrest overview | ACLS-Algorithms.com

-

Kruse, K. E., Batten, J., Constantine, M. L., et. al. (2017). Challenges to code status discussions for pediatric patients. PLOS ONE, 12(11), e0187375. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187375

-

Peddy, S. B., Fran Hazinski, M., Laussen, P. C., et. al. (2007). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Special considerations for infants and children with cardiac disease. Cardiology in the Young, 17(S4), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1047951107001229

-

Berger, S. (2017). Survival from out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest: Are we beginning to see progress? Journal of the American Heart Association, 6(9). https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.007469

-

van Zellem, L., Utens, E. M., Madderom, M., et. al. (2016). Cardiac arrest in infants, children, and adolescents: Long-term emotional and behavioral functioning. European Journal of Pediatrics, 175(7), 977–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2728-4